The high yields explain part of why these three radionuclides get a lot of attention, but there are other reasons as well. The 131I and 90Sr radionuclides also fall in the mass number regions that are favored in the fission process, and their yields are also relatively high.

You can find more detailed lists of direct and indirect fission yields on the Internet a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory site shows these yields for a large number of fission products.

Additional 137Cs comes from the decays of 137I and 137Xe produced directly in the fission process. The 137Te decays to 137I, which decays to 137Xe, which decays to 137Cs. For example, some of the 137Cs is produced by the sequential beta decays of products that come from the initial production by fission of an isotope of tellurium, 137Te. By indirect processes we mean that the 137Cs comes from the decay of precursor radionuclides that were produced in the fission process. As it turns out, if we were to look more closely at just where the 137Cs is coming from, we would find that most comes from the direct fission of 235U, and a small amount comes from indirect processes. A 6 percent yield is a high yield, and 137Cs is a favored fission product. You can see from that table that 137Cs has about a 6.1 percent yield, meaning that for every 100 fission events a bit more than six, on average, yield 137Cs as one fission product. The table below the curve shows some of the expected fission products, arranged from favored fission products to less likely products.īy "favored" I mean those whose fission yields are relatively high. Look at the red curve for the fission of 235U, and you can see the favored mass distribution.

The Wikipedia description of the fission process and the fission product yield curve is helpful. You can find this mass distribution on several internet sites. The first peak expectedly will lie between about mass numbers 90 and 100, and the second peak will fall between about mass numbers 130 and 140. The preferred mass distribution of the products is actually bimodal-i.e., if you plot the yields of fission products of given masses versus mass number, you will generate a curve with two peaks. The two major fragments, which we refer to as fission products, may have a wide spectrum of nuclear masses, characterized by the fact that the fission process does not favor an equal mass distribution between the two fragments.

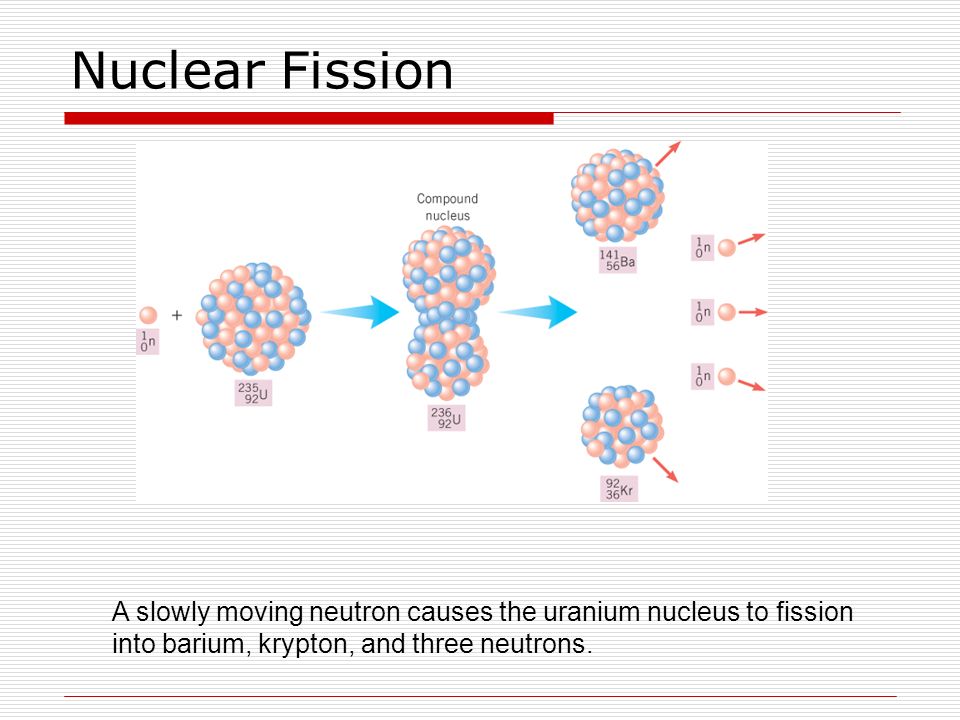

When the 235U captures a neutron, the excitation energy associated with the capture is sufficient to cause the compound nucleus, 236U, to break (fission) into two major fragments, usually accompanied by a few neutrons and some gamma radiation.

#Fission uranium i series

The only significance the actinium series that you mention has is that the parent nuclide in the series is 235U, the uranium isotope relied on in thermal fission reactors. Most reactors in the world are fueled with uranium, with 235U being the most common isotope associated with most of the fission events induced by low-energy neutrons, so-called thermal neutrons. There are indeed many hundreds of possible different fission products produced as nuclear fuel undergoes the fission process in nuclear reactors.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)